Dunes on the Baltic Coast

Coastal dunes are made up of a complex of small scale habitats with a naturally high level of spatio-temporal dynamics. These habitats offer plants and animals unique and varying living conditions and are characterized by their proximity to the sea, their development history and specific plant and animal communities living in them. The dune habitat section of the garden serves to teach about these different interrelationships, which are also an important part of coastal conservation.

Coastal dunes are depositions of almost exclusively pure quartz sand, which originates from the weathering of rocks in mountainous regions and is transported to the sea via rivers. Sea currents can transport sand from the seabed to the coasts with the help of strong winds. There, the surf washes up moderately coarse-grained sand and mixes it with crushed shells, plant material, animal corpses and other debris. The fast drying sand on the surface is then blown inland and settles in the lee of plants growing in the sand.

For the subsequent formation of dunes, some vigorous and clumped groups of grasses form blow-through obstacles, where sufficient quantities of sand are deposited and the grasses grow out of the sand depositions. The deposited sand supplies important nutrients. The sand contains lime and nutrients that are dissolved in seawater or are mixed with fragments of dead organisms and debris. These nutrients are then quickly washed out by rainwater, so that sand dunes are quickly decalcified on the surface and become acidic.

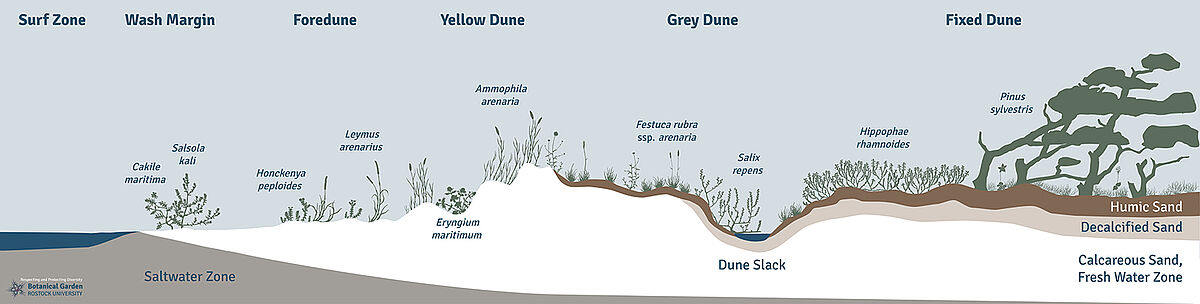

Coastal dunes can only be created in places where sand is deposited by sea currents and the wind blows at a speed of at least 6 m/s over bare sand surfaces to transport the sand further inland. Behind the first inland barriers, which are formed by the wash margin and remaining drift debris, sand is deposited, offering places for the settlement of ephemeral wash margin vegetation, composed of annual nitrophytes.

The first dune formations are created in the lee behind the first plants such as sand couch-grass (Elymus farctus) and sand ryegrass (Leymus arenarius), building low primary dunes. Once marram grass (Ammophila arenaria) becomes established, the primary dunes overflow to a steep yellow dune, creating a wall that can be many meters high. With increasing vegetation cover, the sand becomes anchored in place, and organic matter begins to build up: an increasing content of humus in the A horizon characterizes the further development of the dunes and successively leads to a grey dune. Due to the calming of the sand, the upper layers of sand are quickly decalcified by the rainwater and then become more acidic. These soil-forming processes initiate the further development of the brown dune, in which newly formed clay minerals and iron oxides accumulate in addition to humus, which turn the topsoil brownish and make the soil structure more cohesive.

The vegetation remaining on the primary and yellow dunes is patchily distributed and relatively species poor. Accompanying the sand couch-grass (Elymus farctus) and sand ryegrass (Leymus arenarius), the sea sandwort (Honckenya peploides) also helps toward stabilizing the primary dunes. The marram grass (Ammophila arenaria) joins these salt tolerant species (halophytes) only after there is enough rooting space above the influence of salty groundwater, as it only tolerates low salt concentrations near its roots. In the accumulating yellow dunes there are only a few new species in addition to the marram grass that are also only slightly salt-tolerant, such as the Baltic marram grass (X Ammocalamagrostis baltica), the sea pea (Lathyrus japonicus ssp. maritimus) and the sea holly (Eryngium maritimum). These species tolerate the strong physical stress caused by wind and temporary salt input. Temporary sand surges, on the other hand, are not only tolerated but also necessary because they provide the plants with important nutrients that are essential for continued growth.

At the more inland locations of the grey dune, this sand and nutrient supply is missing for the most part, so that in addition to humus accumulation and rainwater washing out bases, nutrient depletion also occurs. However, the number of species is increasing in this space, with other pioneer grass species such as red fescue (Festuca rubra ssp. arenaria) and bushgrass (Calamagrostis epigejos) as well as undemanding, sometimes xeromorphic land plants. Among the latter are bunchgrass (Festuca polesica), small pasque flower (Pulsatilla pratensis) and kidney vetch (Anthyllis vulneraria), of which the subspecies Antyllis vulneraria ssp. maritima (Hagen) Corb. had been described of being characteristic of the dunes of the Baltic Sea coast; its taxonomic differentiation, however, is not currently recognized.

Older, depleted dune sites, which are occasionally subjected to repeated soil disturbance, are populated by poor soil specialists and acid loving plants (acidophytes) such as crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) and common heather (Calluna vulgaris) as well as, in the case of frequent soil disturbances, gray hair-grass (Corynephorus canescens), which is also characteristic of the fixed dunes and the transition to acidophyte inland vegetation. Trees can also establish themselves in humid dune slacks. In the southern Baltic Sea region, the Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) is common, but the silver birch (Betula pendula) and the pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) can also be found.

In some protected lees of the yellow and grey dunes, dune shrubs can also develop. This shrub layer includes creeping willow (Salix repens) and sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) and indicates a connection to fresh groundwater in the rooting area. They are also ecologically related to the vegetation of constantly wet dune slacks, where the Baltic rush (Juncus balticus) is typically found.

In principle, the dynamics and zonal succession of coastal dunes on the Baltic Sea are similar to those of the North Sea. Due to the specific characteristics of the Baltic Sea as a nearly inland sea, however, the dynamic processes that take place are somewhat weaker. As a result, beach and dune areas are often less extensive and the individual dune elements may be smaller in size and closer to each other, or some successional stages may be missing altogether. The diversity of plant species is often poorer, and the wash margins often only exist as fragments. The Baltic marram grass (X Ammocalamagrostis baltica), a bastard of marram grass (Ammophila arenaria) and bushgrass (Calamagrostis epigejos), is so widespread on the yellow dunes of the Baltic Sea that "pure" marram grass only makes up a small portion of the vegetation. Areas of progressive beach shifting due to strong sand flow are often made up of many low dunes in succession, where the vegetation indicates increasing age, for example on the Darß peninsula. The comparatively low salinity of the Baltic Sea does not play a role in the development of dunes, however, marram grass (Ammophila arenaria) can occur even in primary dunes of the eastern Baltic Sea due to the decreasing salinity.

There are rarely areas where the undisturbed dynamics and development of primary to brown dunes can be observed on the Baltic coast. Many typical plant and animal species that are dune specialists are now threatened with extinction in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The last dunes in the state are mostly in protected areas and are not accessible to visitors due to their susceptibility to disturbances. In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, larger natural dune complexes with authentic successional stages can still be found on the peninsulas Wustrow and Fischland-Darß-Zingst as well as on the islands Rügen and Hiddensee.

Since coastal dunes consist of many diverse habitats in a relatively small area, they are home to a variety of plant and animal species. The fact that these are not well known is due to the fact that almost all coastal areas have been shaped by human influence.

Intensive recreational use endangers the sensitive habitats of the dune ecosystem: The thin vegetation cover of the yellow and grey dunes is disturbed by paths and trampling by visitors. Since the sand deposited by the wind is very loose and can be densely compacted by footsteps, this can also damage the horizontally growing roots of the pioneer species. By clearing the beach of debris, the washed-up plant seeds, their potential germination sites and important nutrients are removed. At the same time, the barren, older dune areas become littered with food remains and excrement. In these areas, nutrients are deposited and alien plant species can take hold. Entire dune landscapes have been completely destroyed by tourism and residential development "with a sea view".

Flood protection measures such as the new construction and planting of dunes also constitute drastic interventions in the habitat. The intentional planting of marram grass (Ammophila arenaria), often mixed with the fast-growing Baltic marram grass (X Ammocalamagrostis baltica), interrupts the natural development and succession of dunes. Furthermore, species introduced for the establishment and decoration of dunes, such as the East Asian rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa) and the Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) from Central Asia, outcompete and suppress native plants.

Beach and dune landscapes and their biocoenoses are now endangered worldwide as a result of the construction of coastal transport facilities and the mining of marine sand deposits. With the advancement of technology and population growth, the demand for sand as a basic resource for people continues to grow, not only for use in the construction of buildings and infrastructure, but also for the manufacture of various products. Desert sand is usually not suitable for this purpose, as the grains are rounded due to prolonged transport by wind, making the sand structure unstable. Sand grains transported by river and sea water, on the other hand, have an angular surface that allows them to hook together and thus provide a stabilization.

Sandy deposits of river and marine origin are being extensively mined worldwide. This has led to the disappearance of beaches and dunes that protect coastal areas in many geologically sand-poor regions of Asia and Africa as well as numerous Pacific islands. There, sand has become a partly illegal and expensive export commodity. It is important to note that due to the high natural dynamics of sea sand, the mining of sand in one location prevents the supply of sand at another location, or can lead to the sagging, sinking and eventual disappearance of nearby untouched sand deposits and beaches. Due to the loss of sand, coasts lose their natural protection against storm surges and are dismantled by the surf. Buildings built on beaches as well as infrastructure (especially near harbors) which cut through the coasts, also contribute to this. In many places, including on the Baltic Sea, this interrupts the sand flow that runs parallel to the coast, which leads to an uneven distribution of sand with shifts in natural deposition and erosion areas along the coast.

The wide beach and dune area at Warnemünde is the result of more than 100 years of stagnation of a sand flow running from west to east at the Warnemünde West pier, which protects the access point to the Rostock ports. From the sand deposits, northwestern winds can constantly create new dunes here, which show typical elements of dune formation and dune vegetation. The Rostock Botanical Garden aims to show this dynamic habitat to visitors in the coastal dune habitat area. On genuine Warnemünde dune sand, we have cultivated rare plant species, which are typical for small habitat niches of the Baltic Sea coast.

In addition to the dune habitats described above, the dune habitat area also includes a stony beach area where you can find characteristic salt-tolerant pioneer species such as the sea kale (Crambe maritima), wild beet (Beta vulgaris, the wild source of the cultivated beetroot) and blue lettuce (Lactuca tatarica), the latter of which has been naturalized from Asia and Eastern Europe. In the lower part of the dune habitat area, there is a small sand-salt meadow, which forms naturally in the protection of sandbanks and dunes, where it is still occasionally flooded by salt water. The typical Baltic Sea species community composition is caused by the salt tolerance of the species and mowing or grazing. Especially under grazing conditions, a characteristic combination of slightly halotolerant meadow herbs can be found, including saltmarsh rush (Juncus gerardii), fewflower spikerush (Eleocharis quinqueflora), sea milkwort (Glaux maritima), strawberry clover (Trifolium fragiferum), saltmarsh flat sedge (Blysmus rufus), sea arrowgrass (Triglochin maritima) and marsh arrowgrass (Triglochin palustris).

The Botanical Garden would like to thank the Geobotany Working Group at NABU Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, the Friends of the Botanical Garden Rostock, the State Office for Agriculture and Environment of central Mecklenburg and all other volunteers for their active support in the redesign of the dune biotope system since autumn 2013!

Text: Dr. Dethardt Goetze